During my immersion in Costa Rica’s healthcare system, I have frequently been asked by locals, affectionately known as Ticos, why I chose Costa Rica. The answer is straightforward. Firstly, I aimed to enhance my proficiency in medical Spanish by learning directly from native Spanish-speaking healthcare providers. Given that 35% of San Diego County residents speak Spanish, I’ve dedicated years to mastering this language, with a specific emphasis on effective patient communication. Engaging in language exchanges isn’t for the faint-hearted; each day feels like a mental workout. Yet, anyone familiar with language learning understands the unparalleled efficiency of immersion. Costa Rican Spanish, with its clarity and few regional variations, has been conducive to my learning. “Me regala un café?” is one particularly Tico variation for ordering a coffee.

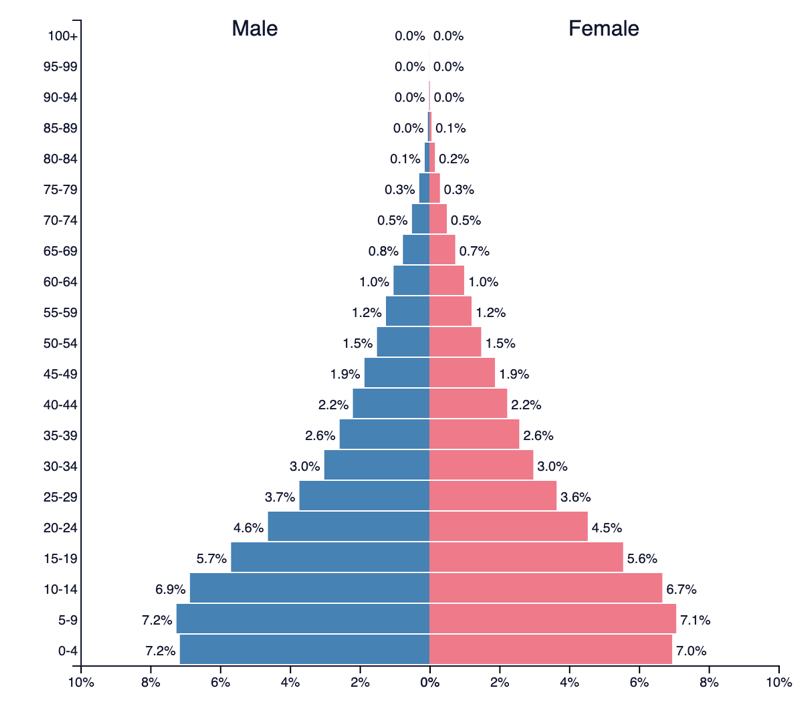

Beyond the linguistic aspect, my second motive for selecting Costa Rica was its healthcare system, particularly the Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social, or La Caja for short. Established in the 1940s, La Caja was designed to provide universal healthcare and social security to all Costa Ricans and residents. Despite its lean structure, the system is incredibly effective, boasting some of the world’s best healthcare outcomes. Over the past 50 years, Costa Rica has managed to reverse its population pyramid, with a life expectancy now reaching 79 years, surpassing neighboring countries like Panama (76 years) and even the United States (77 years). In 2020, Costa Rica’s maternal mortality rate stood at 22.0 per 10,000 births, outperforming both Panama (50.0) and the United States (23.8) in the same year. What’s truly remarkable is that Costa Rica achieves these outcomes while spending about 1/7th of what the Unites States spends per capita on healthcare.

La Caja prioritizes preventive and primary care through its network of EBAISs (Equipos Básicos de Atención Integral en Salud), each serving approximately 4,000 people in a designated area. At the AserríPoas EBAIS where I have been, vaccinations are administered both in the clinic and through community liaison workers. These dedicated liaisons, known as ATAPs (Asistentes Técnicos de Atención Primaria), conduct daily community visits to assess healthcare needs and provide vaccinations to those unable to visit the clinic. One inpatient doctor I worked with remarked that the ATAP had come to see him at home on Saturday to update his vaccines, as they knew that as a doctor he would be unlikely to make it to the clinic and would not be home on weekdays. The emphasis on the ATAP’s role illustrating the system’s commitment to accessible care and community involvement.

The EBAIS physicians deal primarily with primary care – pap smears, hypertension and diabetes management, well child visits, coughs and rashes, and triaging to the emergency room for inpatient admission. Patients are seen consistently and frequently, those with diabetes are seen every three months, and those with hypertension every six. Those who are unable to come to the clinic due to age or disability are seen during the doctor’s weekly in-home visits. La Caja provides medications free of charge, albeit with limited choices. Patients requiring second-line therapies are referred to family medicine physicians for additional options. Another challenge, as is common in many other universal healthcare systems, is long wait times. Currently, this is most felt with imaging services, as radiologists are limited.

To alleviate pressure, Costa Rica also has a private healthcare system operating on a fee-for-service model, offering a wider range of services and medications. Many physicians divide their time between private and public practice. Comparing the private La Católica Hospital to the public Calderón hospital, the private health care system is notably less busy especially at the inpatient level. However, the private health care system complements the public by decongesting long wait times and providing access to a greater variety of medications.

Despite its imperfections, Costa Ricans have immense trust in La Caja, often attributed to the significant improvement in patient outcomes since its founding. This trust is perhaps best exemplified by the widespread admiration for La Caja’s Crema de Rosas, a hydrating cream produced by its independent pharmaceutical laboratory. Costa Ricans swear by its efficacy for various dermatological issues, reflecting not only their confidence in La Caja’s medical products but also their deep-seated trust in the entire healthcare system.

Population pyramid of Costa Rica, 1973 (left) vs. 2023 (right), showing a significant decrease in infant mortality and increase in average lifespan.

Inside of the Clinica de Pavas (public)

Exam room in Clinica de Pavas (public)

A well-fed community dog waiting for a snack in the Aserrí EBAIS breakroom

The emergency room at La Católica Hospital (private) at 10 AM

A La Caja truck used for weekly in-home visits

Mural in La Clinica de Pavas (public)

The infamous Crema de Rosas